Here, have a can of soup.

Nah, we don’t know what’s in it. Could be 30 percent insect parts,

could be seasoned with rat hair, who can say? The ingredients keep

changing anyway. Just pour it into your network and pray.

That, unfortunately, is the current state of cybersecurity: a

teeth-grinding situation in which supply-chain attacks force companies

to sift through their software to find out where bugs are hiding before

cyberattackers beat them to the punch. It’s a lot easier said than done.

The problem has been underscored by the massive SolarWinds supply-chain attack and by organizations’ frustrating, ongoing hunt for the ubiquitous, much-exploited

Log4j Apache logging library. The problem predates both, of course: In

fact, it’s one of the “never got around to it, keeping meaning to”

issues that one security expert – Sophos principal security researcher

Paul Ducklin – stuck an elbow in our rib about when it came time for

end-of-year coverage.

“We’re awash in supply-chain attacks, whether they’re caused by

active and purposeful hacking into software providers to poison code on

purpose (e.g. Kaseya),

or by an inattentive and casual attitude to sucking software components

into our own products and services without even being aware (e.g.

Log4Shell),” Ducklin told Threatpost.

“For years, we’ve batted around the idea that computer software and

cloud services ought to have a credible ‘bill of materials’ that would

make it easy to figure out which newsworthy bugs might apply to each and

every product we use,” he continued.

Will 2022 be the year that finally ushers in the much-longed-for software bills of materials (SBOMs),

the machine-readable documents that provide a definitive record of the

components used to build a software product, including open-source

software?

It’s looking that way, given the Biden administration’s attention to

the issue, and security experts’ beating of the SBOM drum of late.

We pulled together a roundtable of security experts to share a host

of year-end thoughts, and the SBOM issue boiled to the top. What follows

are their thoughts on why SBOMs should be essential, why they’re so

hard to build and maintain, why software makers don’t even know about

bugs in their own products, and whether, maybe, this might be the year

when we finally see SBOM progress.

The Mess that the Lack of SBOM Has Stuck Us With

As it now stands, organizations desperately need new tools to help

them fend off the nonstop stream of attacks that are exploiting

supply-chain vulnerabilities.

Lavi Lazarovitz, head of research at CyberArk Labs, pointed out that

libraries – such as the Log4j logging library at the heart of the Log4Shell internet mini-meltdown – are used ubiquitously. That makes them “prime targets for trojanization,” he said.

“The code is replicated in many applications, and so are the

vulnerabilities,” he said. This year, we’ve also seen several attempts

to take advantage of the huge open-source attack surface with the trojanization of npm packages, as well as ongoing assaults against RubyGems — code repositories for open-source developer building blocks.

Many organizations lack visibility when it comes to what packages are

used and where, which intensifies the impact of vulnerable or

trojanized packages, Lazarovitz said: “Together with the challenge of

patching affected software, a wide enough window is created for both

opportunistic and targeted threat actors.”

Vulnerable or trojanized open-source packages or code libraries “are

usually a solid initial foothold that circumvents perimeter defenses

like firewalls and traditional endpoint-security controls,” he said.

“The malicious code is executed as part of the vulnerable package or

trojanized library, while leveraging the privileges and access granted

to it.”

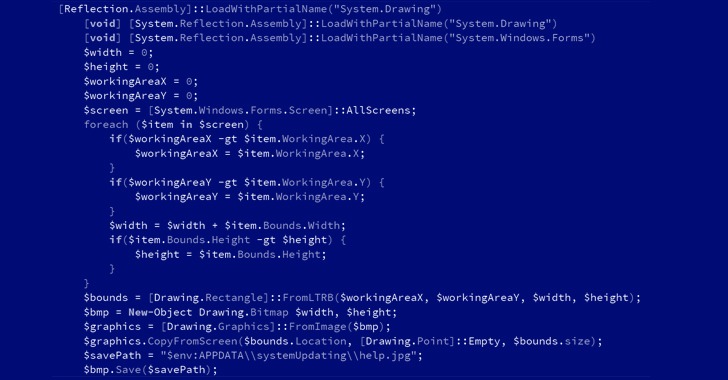

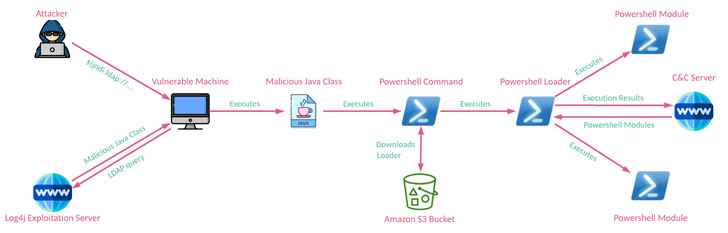

In the case of the Log4j library, the Log4Shell bug allows a

malicious Java class to be injected into a vulnerable, benign process to

run ransomware or other malware on infected systems. In the trojanized URL-Parser library case,

cybercriminals executed credential-stealer code to compromise login

credentials and keys. These and other attack vectors require

organizations “to better monitor and control the code used by developers

to minimize the attack surface and double down on containment of

malicious code within a benign library by securing credentials stores

and limiting privileges and access of both users and services,”

Lazarovitz said.

Tony Anscombe, chief security evangelist at ESET, is hopeful that the

continued parade of supply-chain vulnerabilities and attacks will

create greater corporate awareness on the importance of knowing what

solutions are in use and what technologies may be embedded within them.

“The Kaseya supply chain attack demonstrated that attackers have

ambitious targets that can cause thousands of businesses to be attacked

simultaneously,” he noted. If there’s any upside to the year we just

went through, it’s that these supply-chain attacks are likely to cause

many companies to refresh and audit the requirements placed on

third-party service and software providers, Anscombe forecast.

The Log4J issues are, of course, another force that will raise execs’

questions about auditing and software inventories, as they’ve seen

their IT teams scrambling to scan networks to ascertain if they have

instances of the vulnerable code operating, Anscombe believes.

Why Is It So Difficult to Build & Maintain an SBOM?

Jon Clay, vice president of threat intelligence at Trend Micro, along

with William Malik, Trend Micro vice president of infrastructure

strategies, told Threatpost that currently, product labeling is a

dribbled-out affair. First, there’s no information, then there’s scanty

information and only eventually do we get the software equivalent of a

comprehensive ingredients label.

“We’ll get there with software,” they predicted. “What source

languages are in use? What shared code is included? And eventually they

will be API’ed into a standards-based software asset-management

database.”

As for why SBOMs are so difficult to build and maintain, Eric Byres,

CTO at aDolus, noted that it’s straightforward to generate the SBOM when

a software package is built, but what about software that’s already

been shipped and installed? That category accounts for some 95 percent

of the software used in critical systems today, Byres estimated.

“In these cases, SBOMs generated from the compiled software (aka

binaries) are the only choice for, say, a power company wishing to

manage their security risks or a supplier with decades of existing

software,” Byres said. “The need for these binary-generated SBOMs is

particularly critical in operational technology (OT), where industrial

control system (ICS) equipment have expected life spans of 20 to 30

years. SBOMs are needed for decades of old but still actively used

software.”

That said, when it comes to how many software packages companies use,

what versions are in use and the number of components contained in each

package, the numbers get overwhelming.

“If you are operating a midsized company with a thousand different

software packages and versions in use, and each package has an SBOM with

a thousand components, you’ll have more than 18 billion potential

lookups,” Byres said. And that’s a low estimate, he cautioned: “We

often see SBOMs with 100,000 elements.”

Obviously, checking for the needles of vulnerabilities and

dependencies in these haystacks isn’t viable, he continued, which makes

artificial intelligence a must-have to make lookups efficient and smart.

“For example, if you are searching for vulnerabilities for a SafeNet

licensing module reported in your SBOM, you need to know to also search

for Gemalto and Thales Group, because Gemalto bought SafeNet and the

Thales Group bought Gemalto. And you need to be able to deal with issues

like spelling mistakes – we see lots of cases where developers had

typos in their company’s business name when compiling the software –

these show up in SBOM, making searching vulnerability databases a real

challenge.”

It gets worse, of course.

Liran Tancman, software security expert and CEO of cybersecurity firm

Rezilion, told Threatpost that after an SBOM is developed, it needs to

be maintained and updated whenever a change is made to any application

component – changes that are constant.

“This includes code updates, vulnerability patches, new features and any other modifications,” Tancman described.

Auditing requirements make it even stickier: “Information integrity

is key, so everything included in an SBOM should be auditable, including

all version numbers and licenses,” Tancman continued. “They need to

come from a reputable source and be verifiable by a third party.”

That work is currently done manually, he said, and changes can happen

at any time, he added. “Since these need to be tracked in real time for

the SBOM to be effective, this is obviously a very difficult task.

That’s why it is critical for organizations to look into tools that

offer the ability to have a dynamic SBOM that can incorporate updates

automatically.”

Where Do Orgs Fail with This Dynamic Process?

Converting a mountain of SBOM data into actionable intelligence is a big challenge, Byres said.

aDolus calls it enriching the SBOM: taking the raw ingredient list of

software, determining risk factors for each component and prioritizing

them.

“Matching vulnerabilities to SBOM data is fraught with challenges,

but vulnerabilities are only one risk factor,” he noted. “Some other

software risk factors that we track at aDolus are malware potential,

software obsolescence, country of origin and proof of origin (i.e. did

the software come from the company you think it did?).”

All these factors require complex analysis done at lightning speeds

for millions of components so that users can keep ahead of threat

actors, Byres said.

Unfortunately, today’s SBOMs are static documents that don’t

automatically incorporate updates, Tancman observed. Given that updating

SBOMs isn’t currently a dynamic process, changes have to be made

manually.

The future should bring dynamic SBOMs, or DBOMs, he said. Expect that

to eventually become a requirement, “especially in organizations that

create and update software products regularly.”

DBOMs will also be integrated into a product’s security lifecycle and

be produced automatically at predefined stages, Tancman said, as well

as being interoperable, which will lead to greater adoption.

Why Are Software Makers Clueless About Their Bugs?

Software providers are typically dealing with multiple layers of

providers and likely can demand continuous updates on new

vulnerabilities from the third-party suppliers they deal with directly.

But what about the suppliers to their suppliers, as in, fourth-, fifth-

and sixth-party suppliers, Byres pondered?

And what about all the cases where the developers used open-source software?

“Add in software that’s added via mergers and acquisitions and the

bottom line is many suppliers lose track of the third-party

vulnerabilities in their software soon after it is compiled and

released,” he said.

Byres pointed to the incident with Blackberry in August, when memory bugs in its QNX embedded OS opened devices to attacks.

The company failed to announce the vulnerabilities beyond a few

immediate customers, leaving many using products with the embedded QNX

clueless about propagating vulnerabilities to their own customers.

“But they would have known, if Blackberry had provided SBOMs,” Byres

conjectured. “Both vendors and asset owners need tools like FACT

[Framework for Analysis and Coordinated Trust] that let them quickly

check if they have been shipping, or installing, malicious software

that’s going to damage their reputations.”

Adding to the burden on software makers, Tancman noted, is the fact

that vulnerabilities are constantly discovered, and nobody knows what to

find and track before those vulnerabilities come to light.

On top of that, even if the vulnerability is known/disclosed, it can

be difficult to discover because certain vulnerabilities (like

Log4Shell) can be nested and tough to locate, Tancman said. “But given

the nonstop nature of vulnerability discovery, it is nearly impossible

to know all vulnerabilities in an environment at any given time.”

That’s why building security into the software development life cycle is so essential, Tancman emphasized. If a DevSecOps model is followed in development, there’s less of a chance of finding a flaw in production, he reasoned.

Executive Order Brings Reason for Hope

As luck would have it, 2022 may well be the year that the madness starts to get reined in. Last May, in the wake of the SolarWinds attack, President Biden issued an executive order

advocating mandatory SBOMs to increase software transparency and to

counter supply-chain attacks. As noted by JupiterOne CISO Sounil Yu, writing

for Threatpost in October, it would be one step toward “providing

greater transparency for the software that all organizations must buy

and use.”

The SBOMs will be required to enumerate all of the components –

open-source and commercial – that get glued together willy-nilly in

products. According to the EO, SBOMs will help everybody in the software

supply chain, including those parties who make, buy and operate

software.

“Developers often use available open-source and third-party software

components to create a product; an SBOM allows the builder to make sure

those components are up-to-date and to respond quickly to new

vulnerabilities,” according to the EO.

The EO stipulated that SBOMs will also:

- Enable buyers to perform vulnerability or license analysis, both of which can be used to evaluate risk in a product;

- Enable software operators to quickly and easily determine whether they’re at potential risk of a newly discovered vulnerability;

- Enable automation and tool integration; and

- Be collectively stored in a repository that can be easily queried by other applications and systems.

Security professionals such as JupiterOne’s Yu are encouraged by the

SBOM mandate, he said. Since the EO was issued, software-makers and

buyers gearing up to comply have been trying to make sense of how SBOMs

support supply-chain security.

“Undoubtedly, many see it as a headache, but I believe it is a

sensible safeguard. Part of our problem around supply chains is that we

trust in them too much,” Yu wrote. “We have learned the benefits of a

zero-trust security model and applied this concept to our networks and

endpoints, but we haven’t quite figured out how to do this for our

supply chains.”

He added, “We still rely heavily upon time-consuming questionnaires

that perpetuate the continued reliance on trust as the foundation for

supply-chain security.”

Bob Rudis, chief data scientist for Rapid7, said that the EO also

included a plethora of other, substantive federal initiatives designed

to shore up the nation’s cyber-defenses.

The SBOM mandate will take effect in the second half of 2022 and will

“do nothing short of revolutionizing how software is built, delivered

and identified,” Rudis predicted

The SBOM will be required to accompany all application deliverables

sold to the federal government and will chronicle the entire lineage of

an application, down to the smallest subcomponent, he said.

“Many large healthcare and financial services organizations have

climbed on board the SBOM train and will be following the Federal

government’s lead and also requiring SBOMs as they renew contracts and

acquire new components,” Rudis noted.

“SBOMs will make it possible for organizations to identify vulnerable

components of applications they own and have deployed. Coupled with a

solid asset-management and identification system, SBOMs will make it

much easier to identify where vulnerable components are and ensure they

are protected and updated to stave off threats,” he concluded. “This

will make deployed applications much, much safer and organizations far

more resilient than they currently are. It will take time, but we should

start seeing some benefits immediately as this rolls out in the latter

half of 2022.”

Hallelujah to that: The adoption of SBOMs has already taken far too

long over far too many years of mulling, security practitioners agree.

It can’t come soon enough.

_011922 08:42 UPDATES: Corrected Eric Byres’ title, spellout of FACT acronym, attribution of quotes. _

Photo courtesy of Pixabay.